Catalog # |

Size |

Price |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 033-22A | 5 µg | $236 |

|

| Exhibits correct molecular weight |

|

|

Store in dry form at -20°C. For best results, rehydrate just before use. After rehydration, keep solution at +4°C for up to 1 week or at -20°C for longer-term storage. Aliquot before freezing to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. |

|

| White powder |

|

| Each vial contains 5 µg of protein. |

Several lines of evidence indicate an involvement of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in body weight regulation and activity: heterozygous Bdnf knockout mice (Bdnf(+/-)) are hyperphagic, obese, and hyperactive; furthermore, central infusion of BDNF leads to severe, dose-dependent appetite suppression and weight loss in rats. We searched for the role of BDNF variants in obesity, eating disorders, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A mutation screen (SSCP and DHPLC) of the translated region of BDNF in 183 extremely obese children and adolescents and 187 underweight students was performed. Additionally, we genotyped two common polymorphisms (rs6265: p.V66M; c.-46C > T) in 118 patients with anorexia nervosa, 80 patients with bulimia nervosa, 88 patients with ADHD, and 96 normal weight controls. Three rare variants (c.5C > T: p.T2I; c.273G > A; c.*137A > G) and the known polymorphism (p.V66M) were identified. A role of the I2 allele in the etiology of obesity cannot be excluded. We found no association between p.V66M or the additionally genotyped variant c.-46C > T and obesity, ADHD or eating disorders.

Nam RK, Trachtenberg J, Jewett MA, et al. Serum insulin-like growth factor-I levels and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia: a clue to the relationship between IGF-I physiology and prostate cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(5):1270-3.

OBJECTIVE: A role for the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the regulation of eating behavior has been recently demonstrated. Therefore, the possibility exists that alterations in BDNF production and/or activity are involved in the pathophysiology of anorexia nervosa (AN) and obesity.

METHODS: We measured morning serum levels of BDNF in 22 women with AN, 24 women with obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 30 kg/m2), and 27 nonobese healthy women. All the subjects were drug-free and underwent a clinical assessment by means of rating scales measuring both eating-related psychopathology and depressive symptoms.

RESULTS: As compared with the nonobese healthy controls, circulating BDNF was significantly reduced in AN patients and significantly increased in obese subjects. No significant difference was observed in serum BDNF concentrations between AN women with or without a comorbid depressive disorder. Moreover, serum BDNF levels were significantly and positively correlated with the subjects' body weight and BMI.

CONCLUSION: The BDNF changes observed in AN and obesity are likely secondary adaptive mechanisms aimed at counteracting the change in energy balance that occurs in these syndromes.

Monteleone P, Tortorella A, Martiadis V, Serritella C, Fuschino A, Maj M. Opposite changes in the serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor in anorexia nervosa and obesity. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(5):744-8.

Reduced levels of BDNF in mice cause obesity and behavioral abnormalities including increased aggression and hyperactivity. While it has been shown that the obesity is in part caused by increased food consumption it is still not clear whether defects in other mechanisms involved in the control of body weight homeostasis can also affect this phenotype. Here we report that mice with reduced levels of BDNF do not develop obesity and have normal blood glucose levels if fed over a prolonged period of time the amount of food that control mice usually consume. Thus, hyperphagia appears to be the primary cause of obesity development rather than changes in mechanisms controlling metabolism.

Coppola V, Tessarollo L. Control of hyperphagia prevents obesity in BDNF heterozygous mice. Neuroreport. 2004;15(17):2665-8.

Dietary restriction (DR) extends life span and improves glucose metabolism in mammals. Recent studies have shown that DR stimulates the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in brain cells, which may mediate neuroprotective and neurogenic actions of DR. Other studies have suggested a role for central BDNF signaling in the regulation of glucose metabolism and body weight. BDNF heterozygous knockout (BDNF+/-) mice are obese and exhibit features of insulin resistance. We now report that an intermittent fasting DR regimen reverses several abnormal phenotypes of BDNF(+/-) mice including obesity, hyperphagia, and increased locomotor activity. DR increases BDNF levels in the brains of BDNF(+/-) mice to the level of wild-type mice fed ad libitum. BDNF(+/-) mice exhibit an insulin-resistance syndrome phenotype characterized by elevated levels of circulating glucose, insulin, and leptin; DR reduces levels of each of these three factors. DR normalizes blood glucose responses in glucose tolerance and insulin tolerance tests in the BDNF(+/-) mice. These findings suggest that BDNF is a major regulator of energy metabolism and that beneficial effects of DR on glucose metabolism are mediated, in part, by BDNF signaling. Dietary and pharmacological manipulations of BDNF signaling may prove useful in the prevention and treatment of obesity and insulin resistance syndrome-related diseases.

Duan W, Guo Z, Jiang H, Ware M, Mattson MP. Reversal of behavioral and metabolic abnormalities, and insulin resistance syndrome, by dietary restriction in mice deficient in brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Endocrinology. 2003;144(6):2446-53.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor has been associated previously with the regulation of food intake. To help elucidate the role of this neurotrophin in weight regulation, we have generated conditional mutants in which brain-derived neurotrophic factor has been eliminated from the brain after birth through the use of the cre-loxP recombination system. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor conditional mutants were hyperactive after exposure to stressors and had higher levels of anxiety when evaluated in the light/dark exploration test. They also had mature onset obesity characterized by a dramatic 80-150% increase in body weight, increased linear growth, and elevated serum levels of leptin, insulin, glucose, and cholesterol. In addition, the mutants had an abnormal starvation response and elevated basal levels of POMC, an anorexigenic factor and the precursor for alpha-MSH. Our results demonstrate that brain derived neurotrophic factor has an essential maintenance function in the regulation of anxiety-related behavior and in food intake through central mediators in both the basal and fasted state.

Rios M, Fan G, Fekete C, et al. Conditional deletion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the postnatal brain leads to obesity and hyperactivity. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15(10):1748-57.

A considerable body of evidence links diminished brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling to energy balance dysregulation and severe obesity in humans and rodents. Because BDNF exhibits broad neurotrophic properties, the underpinnings of these effects and its true role in the central regulation of food intake remain topics of debate in the field. Here, I discuss recent evidence supporting a critical role for this neurotrophin in physiological mechanisms regulating nutrient intake and body weight in the mature brain. They include reports of functional interactions of BDNF with central anorexigenic and orexigenic signaling pathways and evidence of recognized appetite hormones exerting neurotrophic effects similar to those of BDNF.

Mukaida N, Sasaki S. Fibroblasts, an inconspicuous but essential player in colon cancer development and progression. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(23):5301-16.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) was studied initially for its role in sensory neuron development. Ablation of this gene in mice leads to death shortly after birth, and abnormalities have been found in both the peripheral and central nervous systems. BDNF and its tyrosine kinase receptor, TrkB, are expressed in hypothalamic nuclei associated with satiety and locomotor activity. In heterozygous mice, BDNF gene expression is reduced and we find that all heterozygous mice exhibit abnormalities in eating behavior or locomotor activity. We also observe this phenotype in independently derived inbred and hybrid BDNF mutant strains. Infusion with BDNF or NT4/5 can transiently reverse the eating behavior and obesity. Thus, we identify a novel non-neurotrophic function for neurotrophins and indicate a role in behavior that is remarkably sensitive to alterations in BDNF activity.

Kernie SG, Liebl DJ, Parada LF. BDNF regulates eating behavior and locomotor activity in mice. EMBO J. 2000;19(6):1290-300.

|

Distinctive pairing of endothelins and neurotrophic factors promotes target innervation during development. Although the sequential action of ET-1 to induce myocyte production of NGF is suggested to promote sympathetic innervation of the heart, more complex interactions of ET-3 and GDNF occur in the patterning of the enteric nervous system. Barbara L. Hempstead. J. Clin. Invest. 113:811-813 (2004) |

|

The functional pleiotropy of BDNF extends beyond the nervous system. BDNF, similar to NT-4, exerts its complex signaling effects via TrkB that is present on neurons. These effects include the modulation of neuronal differentiation, survival, and function. In this issue of the JCI, Kermani et al. (10) report a more complex role for this neurotrophic factor: BDNF can mobilize TrkB+ hematopoietic precursor cells (HPCs) for both hematopoiesis and tissue neovascularization. In addition, BDNF can promote angiogenesis by directly interacting with TrkB expressed on ECs. Dan G. Duda and Rakesh K. Jain. J. Clin. Invest. 115:596–598 (2005) |

|

Cellular and molecular mechanisms of BDNF-induced neovascularization. BDNF was recently implicated in new vessel formation, in both mouse embryos (8) and adult mice (10). In adults, the formation of new vessels in response to BDNF overexpression is the result of both direct effects on TrkB expressed by tissue-resident ECs and the recruitment of TrkB+VEGFR2+CD11b+Sca1+ myeloid HPCs. The latter cells may indirectly promote neovascularization by releasing various factors, including Ang2 and MMPs. Nevertheless, a direct involvement of myeloid HPCs in vessel formation cannot be excluded, as they also have the potential to acquire an EC or mural cell (MC) phenotype. Dan G. Duda and Rakesh K. Jain. J. Clin. Invest. 115:596–598 (2005) |

|

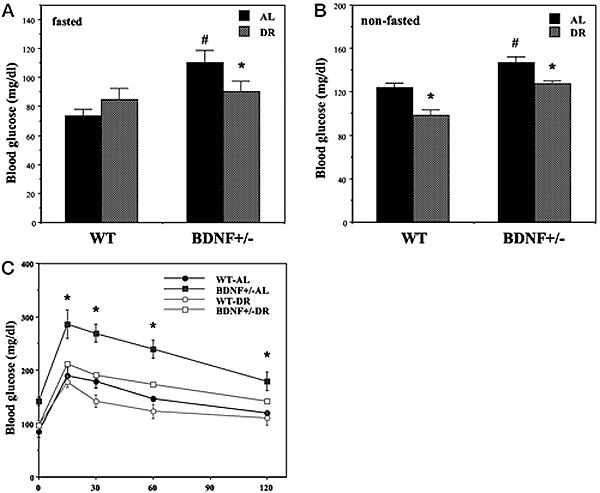

Hyperglycemia and impaired glucose tolerance in BDNF+/- mice are normalized by DR. Wild-type (WT) and BDNF+/- mice were maintained for 3 months on AL or DR feeding regimens. A and B, Glucose concentrations were measured in blood samples taken after an overnight fast (A) or during feeding conditions (B). Note that the scales for the glucose concentrations in the two graphs are different. *, P < 0.01 compared with the value for the same genotype of mice fed AL; #, P < 0.05 cmpared to the WT-AL value. C, Mice were administered an oral bolus of glucose (2 g/kg) and the glucose concentration in blood samples taken at the indicated times was determined. *, P < 0.01 compared with the value for each of the other three groups at that time point. Values are the mean and SEM of measurements made in 8–10 mice per group. Statistical comparisons were made using ANOVA and Scheffé’s post hoc tests. Duan W, et al. Endocrinology. 2003 Jun;144(6):2446-53 |

|

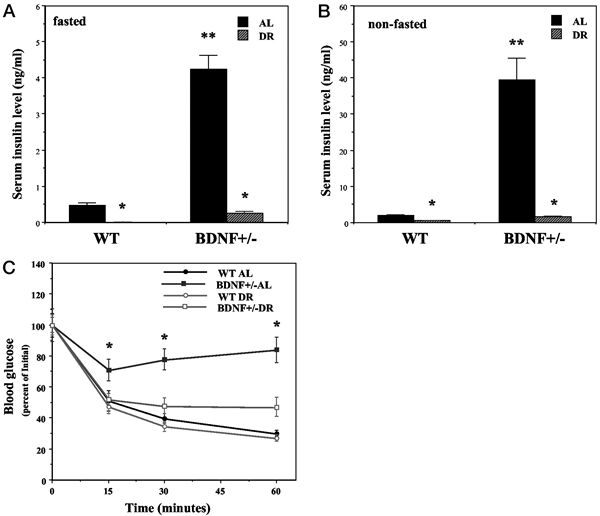

Mice with reduced BDNF levels exhibit insulin insensitivity that is normalized by DR. Wild-type (WT) and BDNF+/- mice were maintained for 3 months on AL or DR feeding regimens. A and B, Insulin concentrations were measured in blood samples taken after an overnight fast (A) or during feeding conditions (B). *, P < 0.001 compared with the value for the same genotype of mice fed AL; **, P < 0.001 compared with the WT-AL value. C, Mice were administered insulin (1 U/kg) and the glucose concentration in blood samples taken at the indicated times was determined. *, P < 0.01 compared with the value for each of the other three groups at that time point. Values are the mean and SEM of measurements made in 8–10 mice per group. Statistical comparisons were made using ANOVA and Scheffé’s post hoc tests. Duan W, et al. Endocrinology. 2003 Jun;144(6):2446-53 |

|

Fat BDNF heterozygous mutant (FBH) mice are obese and show adipocyte hypertrophy. NMR images (A-C) of whole-body horizontal sections are taken at the approximate midline. White density denotes fat, and arrows point to areas of significant fat accumulation in retroperitoneal fat pads. (D-F) Fat histology of inguinal fat pads with the bar representing 70 µm. Quantification of lipid is based on spectroscopy of lipid and water peaks (G) (see Materials and methods). Values represent the mean ± SEM. Wild-type (n = 15), FBH (n = 11) and NBH (n = 8) are labeled accordingly. Steven G. Kernie, Daniel J. Lieb and Luis F. Parada. The EMBO Journal Vol. 19, pp. 1290-1300, 2000 |

|

FBH mice are leptin and insulin resistant. Plasma concentrations of leptin (A), insulin (B), glucose (C) and corticosterone (D) were measured from wild-type, FBH and NBH mice. Blood was drawn and processed as described in Materials and methods. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of 9-23 (wild-type), 12-24 (FBH) and six (NBH) mice. ***p <0.001; *p <0.05. Steven G. Kernie, Daniel J. Lieb and Luis F. Parada. The EMBO Journal Vol. 19, pp. 1290-1300, 2000 |

|

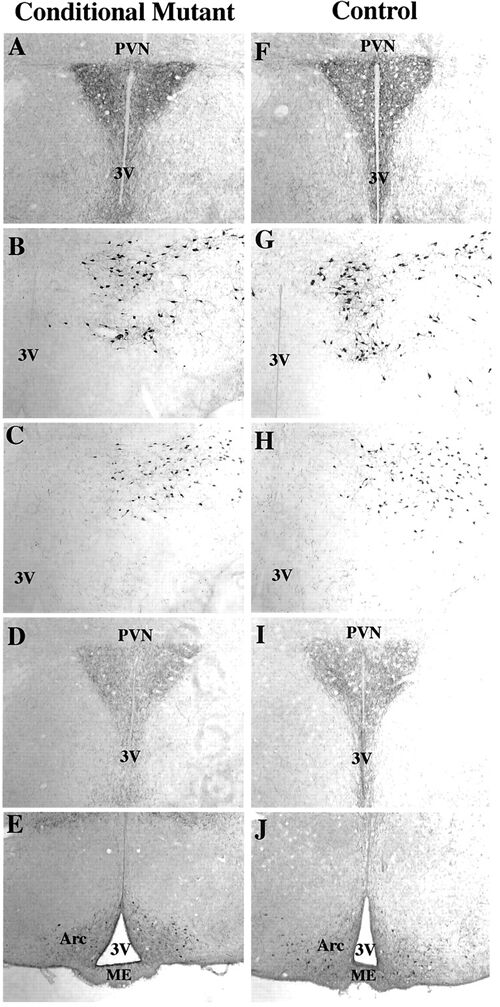

Immunohistochemical delineation of NPY (A and F), MCH (B and G), orexin (C and H), AGRP (D and I) and alpha-MSH (E and J) in the hypothalamus of conditional mutant (A–E) and control (F–J) mice. No differences could be distinguished between the animal groups (n = 3). PVN, Paraventricular nucleus; 3V, third ventricle; Arc, arcuate nucleus; ME, median eminence. Rios M., et al. Molecular Endocrinology 15 (10): 1748-1757 |

No References

| Catalog# | Product | Size | Price | Buy Now |

|---|

Social Network Confirmation